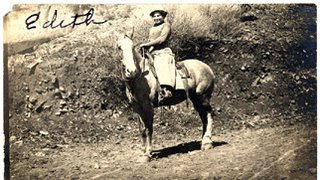

The Ghost of Edith Whitaker

Another story based on fact, as told to me and from my research.

“Did I ever tell you about the ghost I saw? It was at night, we were driving to mom’s house in the Gulch – well, I didn’t think she was a ghost, I

just thought it was one of those hippies living down there.”

just thought it was one of those hippies living down there.”Marylou Nunez was a petite elderly Hispanic woman who even in her best heels, which she wore daily, was just tall enough to drive her 1988 Cadillac. She was from the old school, where a woman always dressed in her finest clothes when going to town, even if were just for a bag of flour. Having grown up in this steep-sided mining town of Jerome, Marylou mastered the art of walking up crumbling inclines and over jagged sidewalks in shoes one wouldn’t dare to even try out on a runway.

Marylou no longer lived in Jerome when she saw her ghost. She had left over forty years prior with her husband when the mines closed. Like everyone else, they migrated to California – followed the work. The town emptied like a fish stand after a case of salmonella. That is everybody left but the real old-timers and the ghosts.

“I saw her walk right in front of the car and go toward the back of mom’s house. I said to Baldo, did you see that woman go into mama’s house? He said, what woman. I said, the woman who just walked in front of the car. She had on a big floppy hat and tall boots. He said, I didn’t see a woman. I asked mama, did you have company. She said no, why, and I told her about what I saw.”

“It wasn’t until some years later that I was talking to the town historian and she wanted to show me pictures of the family who used to live in my mom’s house that I discovered who she was. And there she was, my ghost, Edith Whitaker, sitting on her horse in a big floppy hat and wearing tall riding boots.”

Edith Whitaker wasn’t your typical woman of the 20s. That is, she didn’t fall under any of the categories her town had to offer. She therefore made up her own – what that was, nobody could be sure, it didn’t have a name. What would one call a woman who never married, worked on her own mining claim and drove a motorcycle? An Indian motorcycle that is, straight off Harry Amster’s showroom floor. A motorized bicycle, it was nearly as good as Edith’s horse Babe.

No, if Edith’s type had a name, she certainly wasn’t interested in knowing what it was. What she knew was this – that she valued her independence over all things and that other people should too. In that, she despised the town’s big mining company who controlled everything from the politics to the bread on people’s tables.

She resented it enough to make it her soul purpose for purchasing the ‘other’ newspaper in town; the smaller paper. The main paper, whose weekly cover was completely inundated with the optimistic dogma of the United Verde Copper Company, provided no news at all. It coerced and trapped people into their way of thinking, made puppets of them for their sole greedy purpose. Couldn’t people see this? Maybe what they needed to hear was the truth and nothing but the truth. Hard and real.

Edith’s newspaper would be called The Sun. It, like the mine claim she and her brother owned often took more than it gave back, but for Edith, it worth all of its prospective potential.

Speaking the truth isn’t easy. Waking people from their slumber, shaking them from their dream when dreams may be the only thing they dare to cling to, would prove to be difficult for Edith. Maybe she was a little to harsh and not as diplomatic and unbiased as being a journalist called for, but she had some things to set straight, and, well, while people weren’t playing fair, whose to say who was being one-sided? But the people wouldn’t listen. They didn’t want to see reality, they wanted to their western Utopia, that big break.

No, Edith’s career as a journalist didn’t last long – it was almost a year before her paper was blackballed. Town’s business owners stopped advertising with The Sun in fear of being labeled anti-supportive of the miners and, well, the company.

Edith was hardheaded but she knew when to call it quits. Honesty was a lifestyle she couldn’t afford. In that, wealth never followed Edith, even into old age. Edith didn’t stick around Jerome after the paper collapsed. Her mine was proving unprofitable too and it was time to move on. Some said Edith moved to Ashfork, Arizona where she ran a gas station. She looked hard and haggardly. Certainly life wasn’t easy for an unmarried woman unwilling to play by the rules. But Jerome was where her dreams began and possibly where her dreams continue to this day, even after her death. Is Edith Whitaker still roaming the Gulch looking for something she never could find or she like many of the old-timers who left Jerome and return? None of us will ever know, except maybe Marylou.

No comments:

Post a Comment